The tragic birth of FM radio

What a radio tragedy taught me about UX, AI, and what's next

just chrix.

10/22/20254 min read

Tune an old car radio, and you'll eventually find it: kshhhhhh. That wash of static isn't just noise; it's the sound of a signal lost. It's the sound of "good enough." For decades, it was the sound of AM radio, a sound that a brilliant inventor named Edwin Armstrong nearly died trying to silence.

I recently learned his tragic story. In the 1930s, Armstrong invented FM radio—a clear, rich, static-free signal. He proved its superiority over and over. But the "king of radio," David Sarnoff of RCA, saw FM not as an innovation to embrace, but as a threat to his profitable AM empire. Sarnoff didn't try to build a better product; he used his power to lobby the FCC, change the rules, and move the FM frequency band, rendering Armstrong's entire network obsolete overnight.

This corporate battle crushed Armstrong, who died by suicide, believing he was a failure. But his story isn't just a historical tragedy. For me, as a Digital Product Designer in the auto industry, it’s a powerful and cautionary tale about user experience, innovation, and the very "co-intelligence" I wrote about in my last post.

The Static of "Good Enough" (The UX Lesson)

Armstrong’s story is a perfect UX case study. The problem? A better product isn't enough.

In our world, "AM radio" is inertia. It's the clunky interface drivers are used to. It's the muscle memory for a physical button. It's the "good enough" system that everyone knows how to use, even if it’s full of static.

Our new digital products, connected services, and "FM-quality" experiences are Armstrong's innovation. They are technically superior. But, like Armstrong, we often face our own "Sarnoffs." These aren't necessarily people, but forces: old hardware, legacy partnerships, or even just the driver's established habits.

Sarnoff's move to kill FM teaches us a vital lesson: We aren't just designing a feature; we are designing its path to adoption. We have to obsess over lowering the switching cost for the user. If our new, "better" navigation system is harder to use than just plugging in a phone, we've failed. We’re forcing our users to "buy all-new radios" when they don't want to.

As designers, our job is to build bridges, not walls. We have to guide the user from the static of "AM" to the clarity of "FM" so smoothly they barely notice the switch.

Doomers, Bloomers, and the Ghost of Armstrong (The AI Lesson)

This battle also perfectly mirrors the current conversation around AI. The author of Superagency categorizes people's reactions to AI as Doomers, Gloomers, Zoomers, or Bloomers.

David Sarnoff was the ultimate Doomer. He saw FM only as a threat, a destructive force to his profits. His fear-based actions stalled progress for decades and destroyed a brilliant mind.

Edwin Armstrong was a Bloomer. He saw a problem (static) and relentlessly built a better future—one with high-fidelity sound, stereo, and capabilities no one had dreamed of.

This framework is a warning. Today, the "Doomers" are the Sarnoffs, sowing fear about AI, focusing only on what it might replace. They are trying to "move the frequency band" to protect their own "AM" status quo.

In my first post, I wrote about finding my voice as a "Bloomer." I see AI not as a replacement, but as a "co-intelligence"—a partner to overcome challenges, just as Armstrong wanted to overcome static. The lesson from Armstrong’s ghost is that we must resist the Doomer narrative. When we embrace the Bloomer path, we use new tools not to silence human creativity, but to amplify it.

Beyond the Dial (The Future of In-Car Experience)

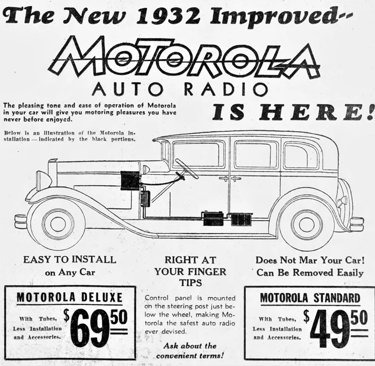

It’s almost 100 years since the first car radio, and we still have AM/FM dials. Why? Because in all its static-filled imperfection, its UX is simple, free, and reliable. It just works.

Our "better" digital solutions—streaming apps, podcasts, satellite radio—often introduce new friction: subscriptions, data plans, Bluetooth pairing failures, and complex menus.

Let’s think about a specific user: the sports fan. Their "job-to-be-done" is simple: "I want to listen to my team's game, live." But the experience is chaos. They have to jump between an AM station for the local broadcast, an FM station for a national game, SiriusXM, or a specific team streaming app. The where is a constant point of friction.

This is where true evolution lies. The future isn't just more apps on the dashboard. That’s just a dial with more static.

The future is a "co-intelligent audio partner."

Imagine this: You get in the car. As your co-intelligence, the car knows you're an NFL fan and that your team is playing right now. You don't press a button. You don't hunt through apps. The system simply says, "Your team's game is on. Want to listen?" and handles the rest. It automatically finds the live broadcast—whether it's on a local AM station, a satellite channel, or the NFL app—and just plays it. It builds the bridge between all those scattered sources and delivers the one thing you care about.

That is our "FM." Our job as designers is to create this curated, intelligent layer that cuts through the noise.

Conclusion: Finding the Clear Signal

Armstrong’s story is a tragedy, but it ends with a note of hope. His "FM" signal, his better idea, eventually won. It just took the world decades to catch up.

We are in a similar moment of change. We have new technologies, new forms of co-intelligence, that can create experiences far clearer and more human than the "static" we've lived with. Our goal—as designers, as writers, as "Bloomers"—is to be the innovators who don't just build the better thing, but who also build the bridge. We must use our tools to cut through the noise, to manage the complexity, and to help every user, and every creator, find their own clear, resonant signal.

References:

1. The Tragic Birth of FM Radio, Article written by Greg Bjerg • Non-Fiction • August 2006

2. Superagency: What Could Possibly Go Right with Our AI Future, Book written by Reid Hoffman & Greg Beato